NEWS

Tracking Russian propaganda in real time The trouble with a new automated effort to expose Moscow's ‘active measures’ against Americans

Pixabay edited by Meduza

What was PropOrNot?

Last November, The Washington Post published a remarkable article about how a “Russian propaganda effort helped spread ‘fake news’” during the 2016 U.S. presidential election, citing a report by “experts” at an anonymous website called PropOrNot.

After initial excitement about the story, the newspaper came under fire for promoting unverified allegations against alternative American news outlets. Critics called PropOrNot a “McCarthyite blacklist.” To PropOrNot, merely “exhibiting a pattern of beliefs outside the political mainstream” was “enough to risk being labelled a Russian propagandist,” Adrian Chen wrote in The New Yorker.

Simply put, PropOrNot bungled its mission completely. On the one hand, the anonymity of the website’s managers invited suspicions about their expertise and agenda. On the other hand, PropOrNot was so transparent about its methodology (talking openly about “red-flagging Russian propaganda outlets” and of course naming specific websites) that it was easy to dispute and dismiss the blacklist. Add to this PropOrNot’s childish, sometimes obscene behavior on Twitter, and it’s no mystery how this project ended up a humiliating dumpster fire.

What is the Hamilton 68 dashboard?

Hamilton 68: A Dashboard Tracking Russian Propaganda on Twitter

The Alliance for Securing Democracy / The German Marshall Fund of the United States

Researchers at The Alliance for Securing Democracy, an initiative housed at The German Marshall Fund of the United States, say they’ve been observing and monitoring “Russian online influence” for three years, so it’s a good bet that they took notice of PropOrNot’s spectacular failure, while developing the “Hamilton 68 Dashboard,” released on August 2.

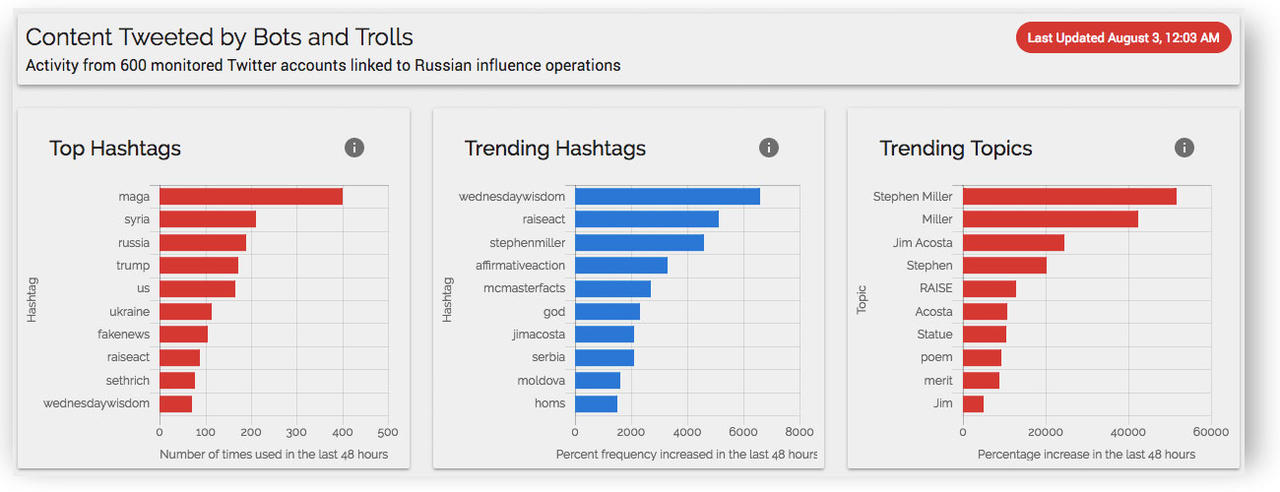

According to The German Marshall Fund, the “dashboard” is designed to “shed light on Russian propaganda efforts on Twitter in near-real time.” The “Hamilton 68” website offers a dozen automatically-updated columns tracking “trending hashtags,” “trending topics,” “top domains,” “top URLs,” and so on.

“Our analysis is based on 600 Twitter accounts linked to Russian influence activities online,” Laura Rosenberger (a senior fellow at the alliance) and J.M. Berger (a non-resident fellow) wrote in a blog post on August 2.

How does Hamilton 68 differ from PropOrNot?

Hamilton 68’s propaganda list is a secret. Unlike PropOrNot, Hamilton 68 does not disclose the identities of the 600 Twitter accounts. All we know of the project’s methodology is that its researchers selected 600 Twitter accounts according to three types (whether there are 200 accounts for each type is unclear): “accounts that clearly state they are pro-Russian or affiliated with the Russian government”; “accounts (including both bots and humans) that are run by troll factories in Russia and elsewhere”; and “accounts run by people around the world who amplify pro-Russian themes either knowingly or unknowingly, after being influenced by the efforts described above.”

The German Marshall Fund says it refuses to reveal the specific accounts in its dataset because it “prefers to focus on the behavior of the overall network rather than get dragged into hundreds of individual debates over which troll fits which role.”

The lack of methodological clarity (for the sake of avoiding “debates”) has already led to some misleading coverage in the media, with outlets like Business Insider reporting that “Hamilton 68 is now working to expose those trolls — as well as automated bots and human accounts — whose main use for Twitter appears to be an amplification of pro-Russia themes,” despite the fact that the website doesn’t actually reveal the names of any Twitter accounts.

For people unimpressed by talk of “600 Twitter accounts,” J.M. Berger told Ars Technica that his team could have expanded the dashboard to “6,000 almost as easily, but the analysis would be less close to real-time.” If that doesn’t sound scientific enough, Berger also emphasized that the 600 selected accounts were identified with a “98-percent confidence rate.”

The German Marshall Fund is no ragtag bunch. Unlike the anonymous potty mouths who launched PropOrNot, Hamilton 68 sports some impressive talent. The project is reportedly the brainchild of Clint Watts, a “former FBI special agent-turned disinformation expert,” who worked alongside J.M. Berger, a fellow with the International Center for Counterterrorism studying extremism and propaganda on social media; Andrew Weisburd, a fellow at the Center for Cyber and Homeland Security; Jonathon Morgan, the CEO of New Knowledge AI and head of Data for Democracy; and Laura Rosenberger, the director of the German Marshall Fund's Alliance for Securing Democracy.

The Alliance for Securing Democracy has a hell of a mission statement. It begins simply, “In 2016, American democracy came under unprecedented attack,” before outlining the organization’s commitment to “documenting and exposing Vladimir Putin’s ongoing efforts to subvert democracy in the United States and Europe.” Putin’s name appear six times in the text.

The Alliance for Securing Democracy also boasts an all-star Advisory Council that includes members like former U.S. Homeland Security Secretary Michael Chertoff, former Estonian President Toomas Ilves, journalist and conservative pundit Bill Kristol, former U.S. Ambassador to Russia Michael McFaul, and former Supreme Allied Commander in Europe Admiral James Stavridis, just to name a few.

With figures like these backing Hamilton 68, it’s no surprise that the project is enjoying a lot of favorable attention from prominent people on Twitter.

What are the problems with Hamilton 68?

The researchers say “the accounts tracked by the dashboard include a mix of such users and is the fruit of more than three years of observation and monitoring,” citing a November 2016 article by Weisburd, Watts, and Berger, titled, “Trolling for Trump: How Russia Is Trying to Destroy Our Democracy.” The text outlines a wide array of Russian “active measures” designed to erode Americans’ faith in their democracy, including efforts as serious as military-orchestrated hacker attacks. Hamilton 68, however, doesn’t claim to track secret Russian hackers, and what we (supposedly) get is relatively underwhelming.

“Attributed government or pro-Russian accounts.” We actually have some idea which accounts Hamilton 68 is tracking, when it talks about this group of Twitter accounts. At the top of the dashboard, there is a widget called “Top Tweets of the Last 24 Hours” featuring a repeating rotation of “top tweets” by Russian state Twitter accounts. At the time of this writing, the accounts displayed belong to the Russian Foreign Ministry, RT America, RT.com, Sputnik International, and RT UK News.

The Alliance for Securing Democracy says its goal with this project is to “spread awareness of what bad actors are doing online” and to help journalists “appropriately identify Russian-sponsored information campaigns.” But what journalist needs a “dashboard” to know that the Russian Foreign Ministry’s Twitter account belongs to “Russian-sponsored information campaigns”? And what is the use of singling out that RT America tweeted about a school explosion in Minneapolis on August 2? Perhaps Russian “active measures” aim to “erode trust between citizens and elected officials and democratic institutions,” and maybe reporting on tragedies or infrastructure failures in America furthers this aim, but characterizing such tweets as “what bad actors are doing” comes eerily close to branding such journalism a Russian propaganda effort.

“Bots and human accounts run by troll factories.” All we know about this category in Hamilton 68’s methodology is that researchers periodically have to “replace accounts that are suspended,” meaning that the dashboard possibly doesn’t monitor a full 600 Twitter accounts at all times, if the deleted bots on the list aren’t replaced automatically. According to Weisburd, Watts, and Berger, bots are a “key tool for moving misinformation and disinformation from primarily Russian-influenced circles into the general social media population,” citing fake reports about a second military coup in Turkey and a gunman at JFK airport.

These incidents stand out, however, because they’re so rare and extreme, and Hamilton 68’s focus on bots risks overlooking the typically futile background noise these accounts produce online. Because the accounts aren’t identified, moreover, there’s no way of knowing if the bots reflected in the dashboard weren’t temporarily hired to promote pro-Russian content before some other client — a shoe company or a vitamin manufacturer, for instance — ordered the latest campaign. This may be a wild, silly hypothetical, but we don’t know any better, with the raw data hidden from us.

“Accounts run by people who amplify pro-Russian themes after being influenced by Russian propaganda efforts.” This is far and away the trickiest, most problematic aspect of The Alliance for Securing Democracy’s new project, and it’s also presumably where researchers wanted most to avoid “debate” about their selection criteria. How do you identify “pro-Russian amplifiers” if Russian propaganda’s themes dovetail with alternative American political views? One of the problems with PropOrNot, in Adrian Chen’s words, was that it unfairly targeted media outlets that “exhibited a pattern of beliefs outside the political mainstream.”

Hamilton 68 tries to dodge this issue by concealing the people it says are “pro-Russian amplifiers.”

J.M. Berger says the project’s selection process has a “98-percent confidence rate,” but that’s an easy claim to defend, when you won’t tell anyone who's on the list.

Kevin Rothrock

No comments:

Post a Comment